Why do we use the organ?

by Scott Scheetz

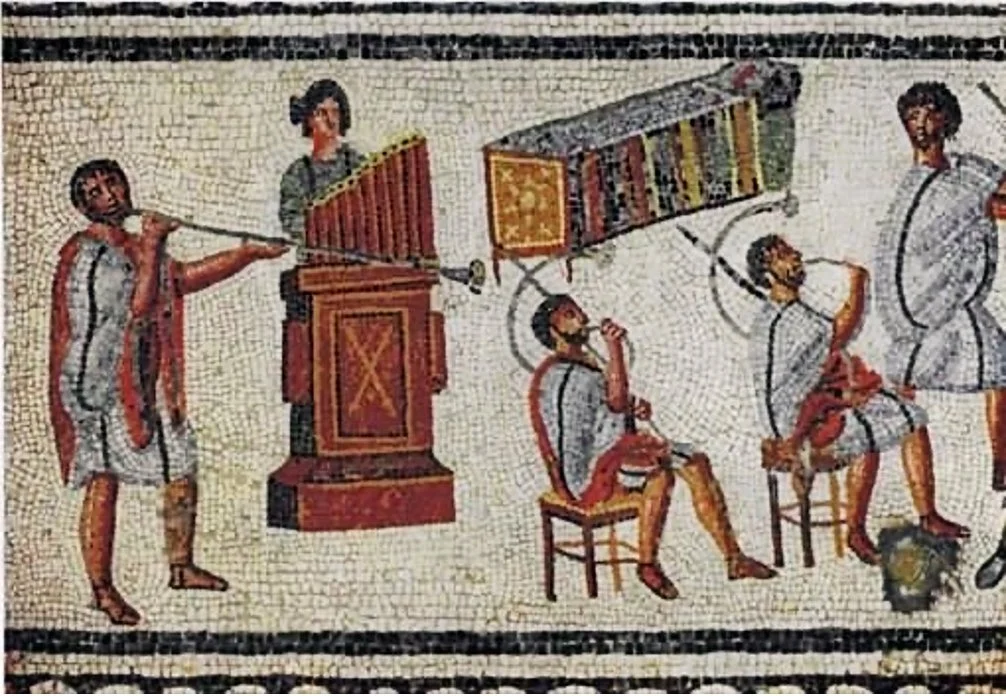

Musicians with horns and a water organ, detail from the Zliten mosaic, 2nd century CE

In Christian worship, we find many different styles of music and instruments. Most western churches with traditional liturgical services have a long-standing history of using pipe organs. The pipe organ is often referred to as the king of instruments and the instrument leads and supports worship and liturgy in ways that no other musical instrument can.

The pipe organ finds its origins in Ancient Greece in the 3rd century B.C. The instrument known as the hydraulis used the weight of water to pump the bellows which provided wind for the pipes. By the 7th century, pipe organs were starting to become common in the Byzantine empire, particularly in monasteries and in some churches. Pope Gregory (540-604) was an early supporter of the organ and wrote highly of the organ and its use in worship. These organs were typically used for festivals and high feast days. A pipe organ with "great leaden pipes" was sent to the West by the Byzantine emperor Constantine V as a gift to Pepin the Short, King of the Franks, in 757. Pepin's son Charlemagne requested a similar organ for his chapel in Aachen in 812, and established the use of the pipe organ in Western European church music.

4th century AD "Mosaic of the Female Musicians" from a Byzantine villa in Maryamin, Syria

Within two hundred years, the organ became common across Europe, and the first English organs were built in the 10th century. The early organ was used for acclamations and the sanctus in worship service, a loud and joyous part of the liturgy, a perfect time to use the instrument! The use of the organ beautifully follows the command in David’s psalm, “Make a joyful noise unto the Lord, all ye lands. Serve the Lord with gladness: come before his presence with singing” (Psalm 100).

By the 13th century, many large churches featured multiple organs both in the front and the back of the church. Some had as many as 3 or 4 pipe organs throughout the church. The church at Guadaloupe is said to have had eight organs, and the cathedral at Seville no less than fourteen pipe organs! Sometimes the organs were used in alternation with one another or with voices, allowing for song and music to join in from all parts of the cathedral. In some cases, multiple new organs were built in other locations inside the church so worship services could continue while the building was being repaired or renovated. Many of these instruments featured very ornate casework, and like the buildings, they increased in size and grandeur to represent the majesty and glory of God. As time passed, pipe organ design and scale grew larger and larger and by the 15th century, the pipe organ was getting substantially closer

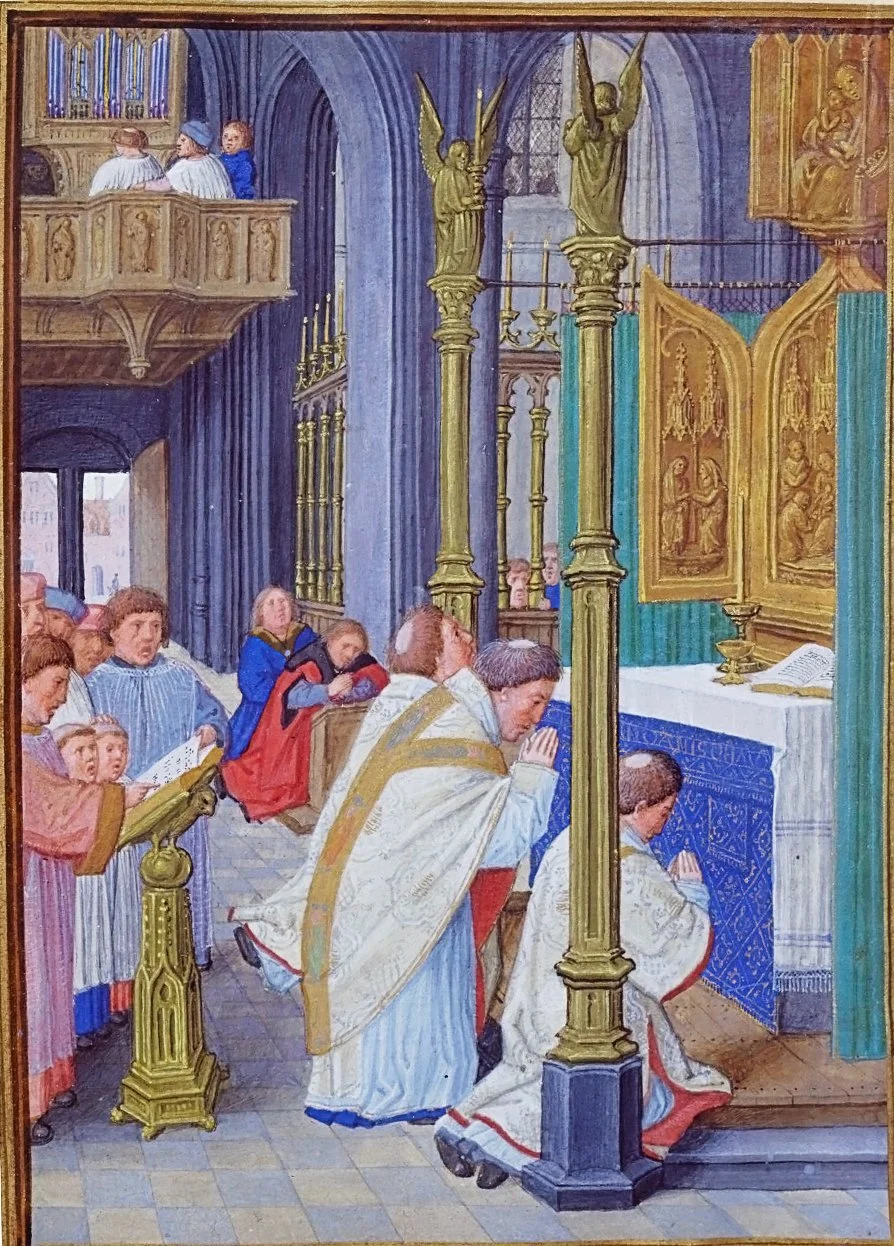

to the instrument we know today and its use in church worship was firmly cemented in place. I love this beautiful painting from The Book of Hours in 1525 where we can clearly see the pipe organ in the balcony. Its inclusion shows the significant role of organs in Christian Worship.

‘The Mass’ from Book of Hours, c. 1525

So why do we still use the organ today? What benefits does it have over other instruments, particularly the piano? First is the organ’s ability to greatly change both volume and color in a way that would otherwise require multiple instruments. In 1873, Rev. H. W. Beecher gave a lecture on music in churches, and described how the sound of an organ is like that of an orchestra but only requires one person instead of 50. The organ’s versatility in volume and color allows for flexibility in accompanying choral singing, congregational singing, and soloists, as well as solo repertoire for service music. The organ’s role is to encourage and support choral and congregational song as well as aid in the musical expression of the words. This is what is known as text painting. The organ allows for creative registration options (selection of sounds or colors) which can help paint and demonstrate the text of hymns during the liturgy. Careful thought and consideration of the text results in colors from the organ that support the hymns and add variety of sound on different verses. One example is a dark, thicker, and lower timbre for text about suffering and pain, and a lighter sound for texts on peace or love. Another example is higher pitched and brighter sounds when the text talks about heaven or the skies above. The second verse of the hymn “This is My Father’s World” has the text: The birds their carols raise. On this verse, I typically reinforce that with a solo flute sound that mimics the sound of a bird. This ability to change color sounds also allows the organist to aid congregational song by reinforcing the melody with a completely different sound, such as a solo tuba, trumpet, or flute. A piano cannot change the color or timbre to represent different texts, nor can the piano create multiple different colors and sounds at the same time. It can only change volume and produce one sound, whereas the organ can change color and volume.

Second, the organ is a superior instrument for accompanying singing and teaching songs than the piano because of the way in which the sound is produced. A piano is a percussion instrument as it uses hammers flung at strings to produce pitches. This results in each note played having a sharp attack. Typically, choral conductors and organists try to encourage the production of a smooth legato and sustained sound when singing hymns, anthems and solos. With its sharp attack and percussive nature, the piano works against us and results in non-sustained singing with poor breath support. Melodies that are supposed to be legato become detached. On the other hand, the organ produces its sound by blowing air through a pipe. This process eliminates the percussive attack of each note found on the piano, and better relates to singing as both utilize moving air to produce sound. In his book, The King of Instruments, Peter Williams relates that the organ’s ability to produce a sustained sound makes it superior to other instruments to accompany singing. The organ’s similarity to human breath must have surely played a role in its adoption for church music. In fact, one of the oldest organ stops (or sounds) is the vox humana, which translates as human voice, and was an early attempt at recreating the human voice. The organ’s sustained sound can reinforce good breath support and legato singing. People sing what they hear: if they hear a sustained and legato sound from the organ, there is a greater potential for people to sing well.

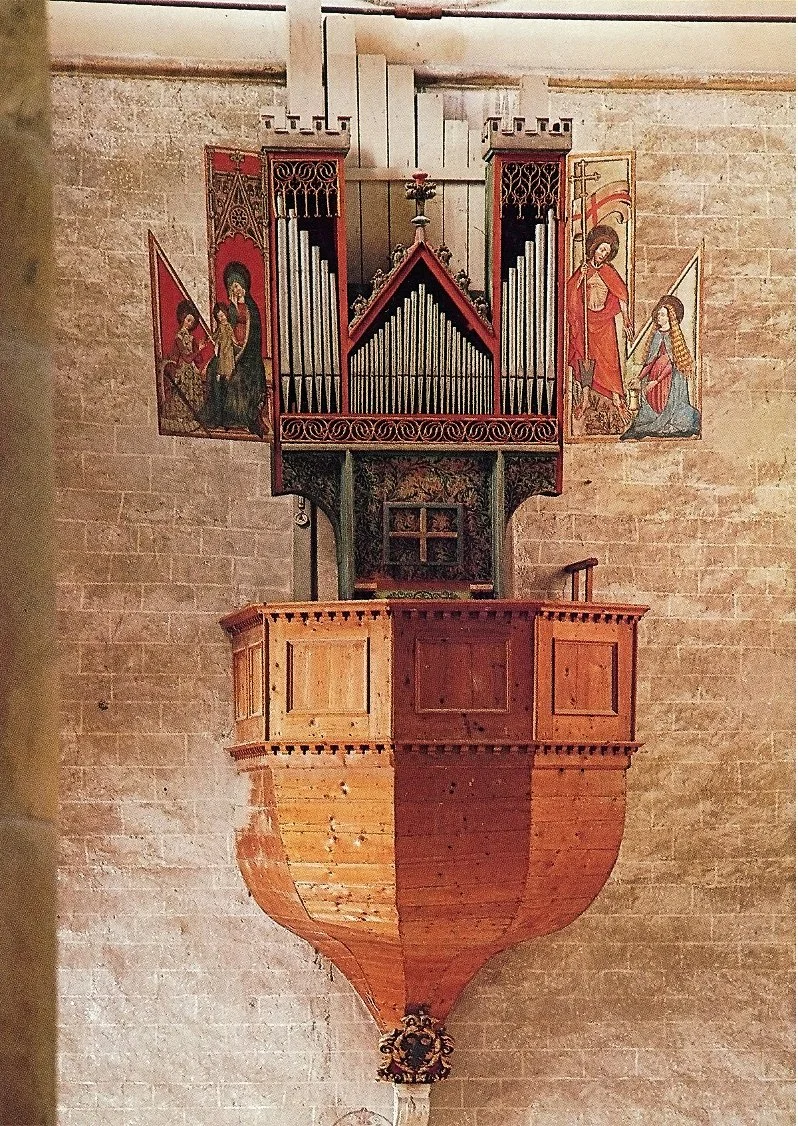

The world’s oldest playable pipe organ built in 1435

Third, the organ is a prime choice due to its theological implications. Williams remarks at the end of his book, “For [the organ’s] spiritual role, an advantage was that the player does not himself produce the sound but is merely an agent through whom the pipes speak--a servant not a performer.” This of course parallels the idea that God speaks through His people. Good works come from God, and people can be the vessel through which God acts. In addition, the concept of the wind of an organ representing the breath of God can be seen in early drawings which depict the organ as the most sacred of instruments. While these theological implications might be hidden behind the liturgy, the idea of me as a music minister and organist being a servant of God is something I take very seriously. Before each service, I always pray that what I say, do, sing, and play during a worship service would give God glory as well as enable congregational worship and song, enrich the worship service, and help deepen people’s relationship with God.

The organ also brings a long history of written music, and a rich tradition of improvisation to the liturgy. From J.S. Bach’s Orgelbüchlein of choral preludes, to Marcel Dupre’s 79 chorales and many other compositions, one can find sacred music suited for scriptures, hymns, and particular days of the church calendar. This enables the music, the scripture, and the sermon to form a seamless liturgy in which all of the elements are connected, enriching the worship experience. In addition to existing written music, the French tradition of service music is heavily focused on improvisation based on hymns and chant as a means to connect the liturgy into a seamless unit. The organ suits this task extremely well due to its wide range of color and timbre all at the fingertips of one person. The organist is able to become the composer, conductor, and the orchestra, allowing them to adapt to the needs of the service, congregation, and the atmosphere present in the room.

Finally, the organ brings a sense of grandeur to the service which no other instrument can provide. Its sheer size both in regards to physical footprint and sound set the tone of the service. When we enter many churches, the first thing we see or hear is the organ. Organs are built as a symbol and testament of God’s power and glory and through their massive size and sound, and praise and glorify God in a way that no other instrument can.

Soli Deo gloria!